Written by: Samantha Martinez, Environmental Educator

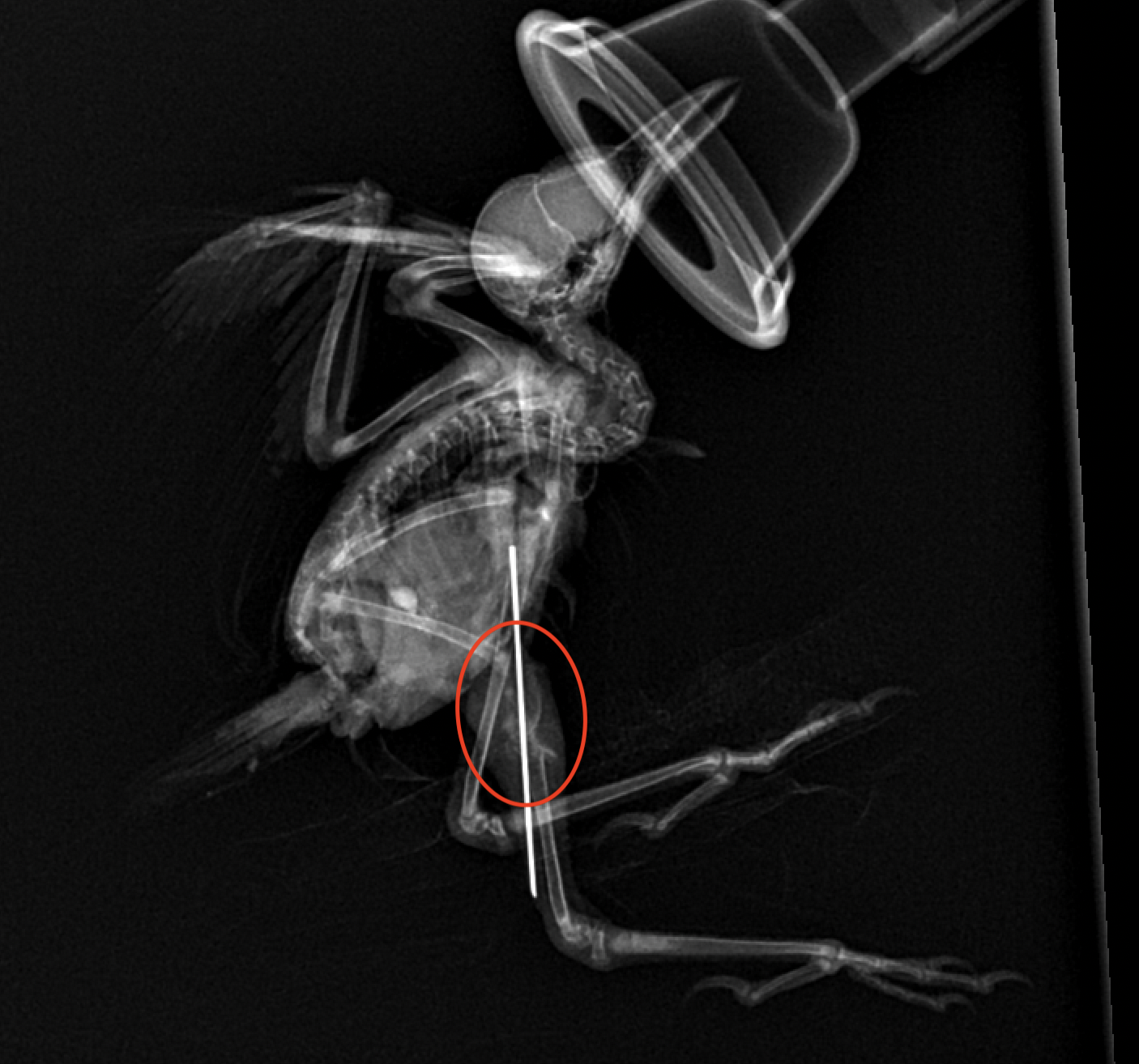

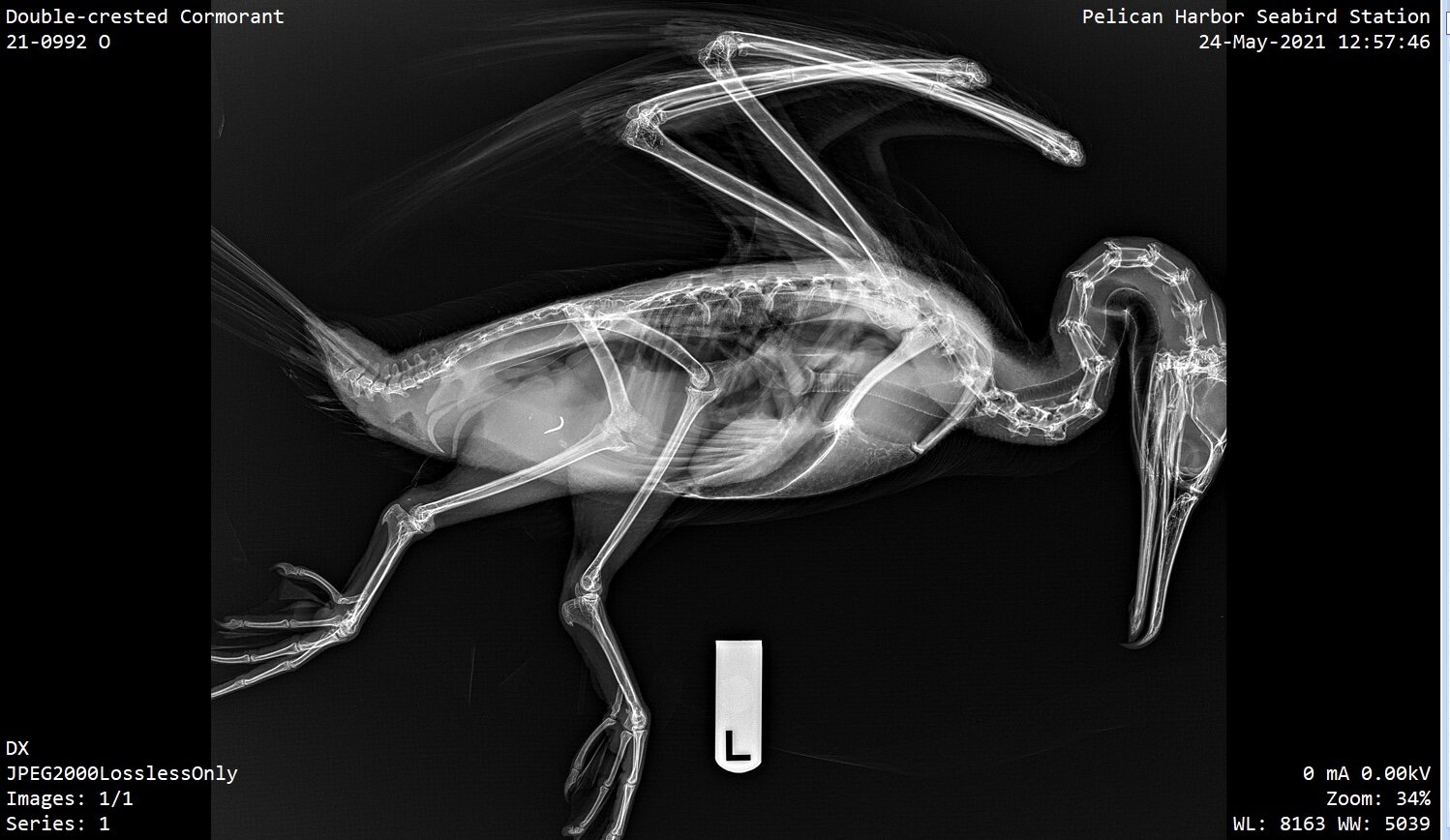

“Out of sight, out of mind”. It is how we feel when we stuff our laundry under our beds and walk away from a stressful situation. However; it is not the philosophy we should take up when it comes to the effect of pesticides on the environment around us. Here at Pelican Harbor, these effects often show up right at our doorstep, either in the form of malnourished nestlings or suspected pesticide poisoning cases in both young animals and adults. In these cases of animals brought in to us, we can begin treatment immediately to flush out these toxins from the animal’s system with fluids and vitamins. Once healed and released back into the wild, we have to hope that the patient doesn’t have another run-in with the number of ingestible poisons that can be found in urban areas such as Miami.

You may remember or have heard of the disastrous effects that the pesticide DDT had on bird populations, most notably on the eggs of the Bald Eagle and the Brown Pelican, bringing both species to the brink of extinction. This synthetic chemical would not usually harm an adult bird outright but would affect the calcium metabolism in adult birds leading them to lay eggs that were not strong enough to withstand the weight of the parent incubating it. Though these effects were pertinent throughout the 1940s when DDT was first developed, it was not until 1972, two years after the establishment of the EPA and ten years after the release of multiple studies on the aftermath of the pesticide, that DDT was banned from use in the U.S. When we look at the commonly used pesticides today for both agriculture and personal gardening it is hard to say that we are not also ignoring the negative side effects of these pesticides on the wildlife around us.

One of the most commonly used pesticides in home gardening in the US is Permethrin, a type of Pyrethroid. This is a family of synthetic pesticides meant to mimic and enhance the effect of the natural pesticides found in chrysanthemum flowers. This insecticide works by allowing sodium ions into the neural membrane of the victim in copious amounts, leading to depolarization and hyperactivity of the neuron. Eventually, after muscle spasm caused by this neural incapacitator, the victim will pass away. Pyrethroids have been thought to be an effective and safe insecticide due to their lack of toxicity when exposure is dermal or respiratory. Meaning, as long as you don’t mistake it for your margarita mix, it’s not going to have an obvious effect on your body. Most adult animals can process the chemical as long as it is not ingested orally or injected directly into the animal. However, this chemical can still be harmful to people. Pyrethroids are unaffected by secondary treatment in municipal waterways and therefore trace amounts can be found in most drinking water where the chemical is used. It has also been reported that young children with asthma or infants can have adverse effects from even minimal exposure.

Though Pyrethroids are supposed to be a targeted insecticide it does still manage to have an effect on the animals other than the intended targets. For example, it has been shown time and time again that this toxin has a negative effect on our already dwindling bee population. The most susceptible classes of animals besides insects to this specific toxin are amphibians and plankton, which are all vital members of their food webs and most susceptible to chemical runoff in the water. Pyrethroids can also be very lethal to cats since their liver cannot process it as well as that of other mammals. Lastly, when it comes to our feathered friends, while this specific toxin is able to be expelled from their bodies quite quickly with minimal effect, it has been shown that the decrease in the insect population has led to more deaths in first-year insect-eating songbirds.

It is not only our backyard pesticides that have a negative effect on the environment and we cannot solely or even heavily place blame on the individual gardener attempting to rid his home and yard of pests. Agricultural use of pesticides like neonicotinoids, a chemical closely related to nicotine, has continued to increase despite the overall decrease in pesticides themselves over the past two decades. Neonicotinoids, neonics for short, which are bred into the seeds of the crops, are used in 44% of farms in the U.S. This allows cheaper protection for crops such as soy, corn and canola but also has a severely adverse effect on the local environment since only 5% of the chemical is cultivated in the plant and the rest is lost to water runoff at the seed stage. Neonic then finds itself in local water sources, affecting animals from the bottom to the top of the food chain.

Besides being aware of the crops we buy and the chemicals they may harbor, there is little we can do to affect the pesticide use of large agricultural based businesses. What we can do is take a look at our own yards and neighborhoods and choose to treat them with natural, less harmful pest preventions such as companion planting, using soaps and plant oils or introducing predators to your pests such as ladybugs. Whatever you choose to do for your home, it is important to keep in mind that when it comes to the dangers of pesticides, it did not stop with DDT.

Sources:

Connected, Science, et al. “Organic Gardening and Alternatives to Pesticides.” Science Connected Magazine, 6 June 2021

“The Origins of EPA.” US EPA, 9 July 2021

“The Same Pesticides Linked to Bee Declines Might Also Threaten Birds.” Audubon, 14 May 2019

Wikipedia contributors. “Pyrethroid.” Wikipedia, 15 Apr. 2021